Why Everyone with Six Figures to Invest Should Consider Angel Investing

[The following is an edited excerpt from David S Rose’s book Angel Investing: The Gust Guide to Making Money and Having Fun Investing in Startups.]

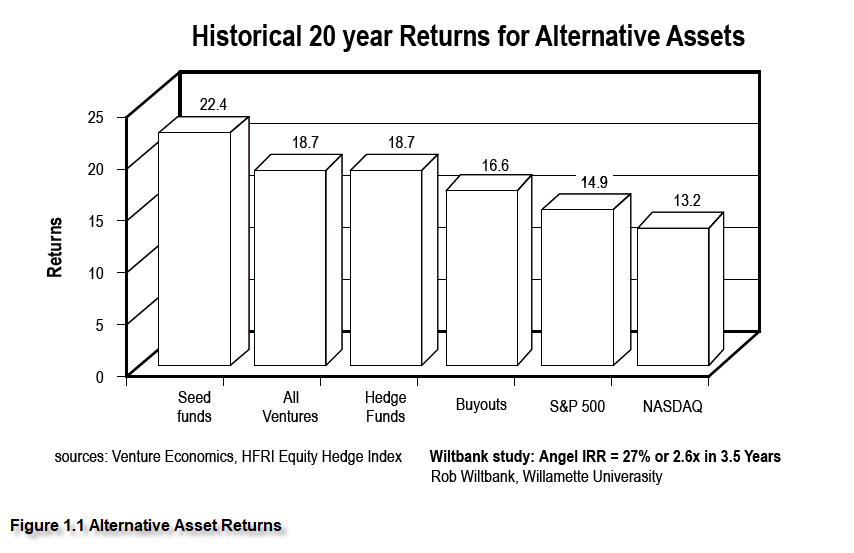

Angel investing in the past few years has moved from an arcane backwater of the financial world to a business arena that receives coverage in mainstream newspapers and hit television shows such as ABC’s Shark Tank. Today, any sophisticated investor with a portfolio of alternate assets should consider direct, early-stage investments in private companies as one potential component of that portfolio. Why? Because multiple studies have shown that over the long run, carefully selected and managed portfolios of personal angel investments—even those without a giant hit such as Pinterest—produce an average annual return of over 25 percent. Compared to average annual returns of 1 percent from bank accounts, 3 percent from bonds, 7 percent from stocks, 10 percent from hedge funds, and even 15 percent from top-tier venture capital funds, that is an impressive number. See Figure 1.1.

What is even more interesting about angel investing is that, unlike sitting back and clipping coupons, or reading the stock listings in the daily paper, being involved as a part owner of an exciting startup company can be a great deal of fun. You get a ringside seat at a venture that is out to change the world, direct access to company CEOs who may become the corporate magnates of tomorrow, and early access to the latest products and services before they become generally available. You may even have the opportunity to advise and mentor a company as it develops, pivots, and changes its business plan in response to real market experience.

By now, this must sound too good to be true: outsized returns and having fun—what’s not to like? But here is the sobering reality: a large majority of self-proclaimed angel investors actually lose money, rather than make anything at all! How can these two facts be reconciled? Simple: those 25 percent-plus returns are “over the long run, on carefully selected and managed portfolios of angel investments.” In practice, however, most people who call themselves angel investors do not carefully select or manage their investments, do not take a long-term view, and do not have a clue about how to approach angel investing as a serious part of an alternative-asset portfolio. But you want to understand how to engage in angel investing as a serious part of your investment allocation. So let’s begin with the basics.

Get started investing in startups with Gust's Angel Guide. Education, community, and vetted deal flow.

What exactly is angel investing?

Angel investing is when individual people (as opposed to professionally-managed investment funds, corporations, governments, or other institutions) invest their personal capital in an early-stage company—often known as a startup. Angel investors are individuals who invest their own money, typically in small amounts, and typically very early in the lifecycle of a company.

Angels find investment opportunities through referrals from people they know (such as CEOs of companies in which they’ve already invested), through attending regional or national events at which early stage companies launch their products, by being approached directly by ambitious entrepreneurs, through joining with other angel investors in organized angel groups, or, increasingly, by participating on reputable online early-stage investment platforms such as Gust. All of these techniques for identifying angel-investment opportunities, and many others, will be described in greater detail in Chapter 5.

The fact that angel investors use their money to back companies they hope will grow and bring them significant profit is not, in itself, unusual. Most mainstream investors do the same. They invest in blue-chip companies like Apple, Google, GE, and Coca-Cola, or in mutual funds that support an array of companies, hoping their money will grow as these businesses grow. The crucial difference between these mainstream investors and angel investors is that angels invest in startups—companies that are relatively new, small, and privately held (rather than publicly traded in a marketplace like the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ). Because these companies are like tiny plants, striving to become giant trees, the first investments in them by angels and others are often referred to as seed investments.

Unlike public companies, startups are often little known. They generally do not appear on the cover of Forbes or Fortune, and you won’t hear them talked about by stock analysts on cable TV or even by your favorite broker. So understanding what these startup businesses are like, where to find them, and how to identify those with significant growth potential is one of the keys to being a successful angel investor.

The world of startups and the ways in which angels and startups work together is a fascinating topic—and one in which change is constant. The stage at which an angel would typically begin supporting a startup with a cash investment has changed over the last few years as a direct result of the decreasing cost of starting up a scalable company using current technology. In the past, when the only way to get a company going was to spend cash, early investors would often have no alternative to “taking a flyer” and supporting an entrepreneur who had only a vision and a plan.

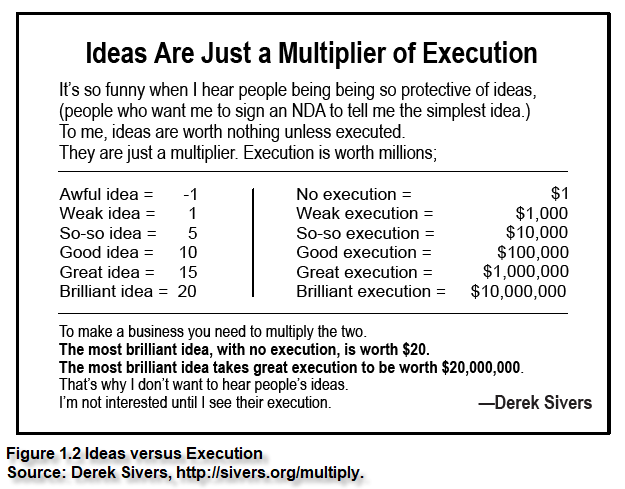

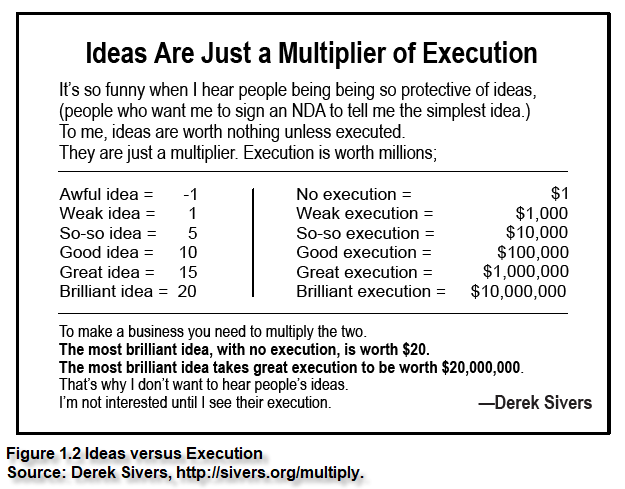

But today, with technology providing startup businesses with virtually free hosting, bandwidth, tools, and marketing (or at least free enough to get you started), the bar for a company to be considered fundable has been raised because it is so easy for anyone to get started. Since the large majority of opportunities with which angel investors are presented already have something going for them (a finished product, initial customers or users, perhaps even revenue), it is challenging for entrepreneurs with only an idea. Why should an angel take the added execution risk if he or she doesn’t have to? Derek Sivers, an entrepreneur, writer, and frequent speaker at the TED conferences, summed up the idea versus execution relationship in a seminal blog post from which I’ve borrowed this eye-opening table for Figure 1.2.

Because of this, many companies in their earliest stages are unable to attract financing from angels and other professional investors. Consequently, so-called Friends and Family rounds of investment are the most common way (other than the founder’s own capital) to fund a startup, and account for nearly a third of all financings. (A further explanation of the various stages of financing a startup in more detail is in Chapter 4.) Friends and Family investors do not base their investment on the merits of the business, but rather on their support for the entrepreneur. By contrast, the professional angel investor focuses on the long-term strengths and prospects of the business, in much the same way a mainstream investor picks stocks based on an evaluation of the strengths and prospects of the companies issuing those stocks.

As with investors in public company stocks, angels are part-owners of the companies in which they invest. The difference is that $10,000 invested in Google might buy you 10 shares of stock, representing one 33-millionth of the company. That same $10,000 invested in a promising startup might buy you 10,000 shares of stock, representing a full 1 percent of the company’s ownership.

With that low a cost of entry, it is fair to ask if one angel ever becomes the majority owner of a startup. The short answer is virtually never. While there are, indeed, individuals who have put a million dollars or more into one company, the vast majority of serious angel investors play with much smaller numbers. This is because investing at the seed and early stages of a company’s life cycle is risky—the large majority of such investments fail completely. Angels therefore try to invest in at least 20 to 80 companies, thereby limiting the amount that will be lost on any one.

The average individual angel puts in about $25,000 per company, typically with 5 or 10 angels joining together to make up the investment round. (Many angels participate in angel groups or syndicates of various kinds. It’s a very effective way to pool insights, ideas, connections, and other resources, and it enables angels to invest more powerfully than they could as individuals.) A 2009 survey showed that the average total round size for an angel group is about $275,000 . . . although increasingly groups are joining together to syndicate deals in order to raise larger rounds.

Outside of that context, the range is wide, with solo angels investing anywhere from $5,000 to $500,000 (or more) in a given company. “Super Angels”, a misnomer usually applied to experienced investors who manage micro-venture funds, seem to average about $100,000 to $200,000 per investment. It is only when you get into the territory in which venture capital companies operate that you’ll find early-stage investments getting close to $1 million from a single source.

So, in a nutshell, an angel investor is a private individual who invests significant, but modest sums, usually in five figures, in a variety of startup businesses. These investments collectively form a portfolio that, over time, will likely include both winners and losers. The key to being a successful angel is to have enough winners to more than offset the losers.

Can You Really Make 25 Percent a Year?

The essence of successful angel investing begins with recognizing and accepting one hard fact: Your chance of making a profit by investing in startups is somewhere between very, very slim and almost negligible if you’re talking about investing a very small amount in one company. Those odds increase significantly once you diversify your investments (even if they are relatively small) in dozens of companies.

Why is this the case? It is because a majority of all new, angel-backed companies fail completely, so if you invest in only one company, the odds are that you will lose all your money, not just “not make a profit.” But when a company succeeds, it has the chance to really succeed, and return many times the initial investment. This is known as a “hits business”.

So how much of a return does an average angel investor earn?

The data needed to answer this question doesn’t really exist. because (1) there is no such thing as an average angel investor, and (2) there is currently no way to track the activities or record of individual investors.

That said, a rough summary of key statistics from Gust describing the activities of typical professional angel investors would be as follows:

– Individual angel investors receive anywhere from zero to 50 pitches a month, depending on how actively they promote their availability and how accessible they make themselves.

– Organized angel investment groups similarly might typically receive between 5 and 100 submissions monthly. All angel groups taken together probably receive about 10,000 submissions monthly. All individual angels taken together probably receive about 50,000 funding requests each month.

– Organized angel groups typically look at around 40 companies for each one in which they invest (compared to 400 for venture capital firms).

And of all requests for funding received by an angel group each year:

– 30 percent are invited for a preliminary screening review.

– 10 percent are invited to pitch to the full group.

– 2 percent receive funding from at least some members of the group.

On average, individual investors in U.S. angel groups invest about $35,000 per company, and members of a group taken together invest about $300,000 per company.

Once an investment is made, the rough outcomes (averaged from several independent studies of angel returns) are:

– 50 percent eventually fail completely.

– 20 percent eventually return the original investment.

– 20 percent return a profit of 2 to 3 times the investment.

– 9 percent return a profit of 10 times the investment.

– 1 percent return a profit of more than 20 times the investment.

Where do these numbers—assuming they are approximately accurate—leave our mythical average angel investor?

The reality is that results in angel investing tend to bifurcate.

The large majority of self-described angel investors, both domestically in the United States and internationally, are either new to the field, not taking it seriously as a financial business, not in it for the long haul, or are not willing to continue investing until they have a fully diversified investment portfolio. For those people, returns tend to be flat to negative.

By contrast, professional angel investors, who follow the approach described in this book, invest calmly, steadily, relatively rationally, over a long period of time, with a strong knowledge of both investment math and early-stage realities. They tend not only to make money, but do quite well: in fact, the average return for a comprehensive, well-managed angel portfolio is between 25 and 30 percent internal rate of return (IRR).

Who Can Be an Angel?

Because angel investing is very risky (unless you take the approach described in this book, and invest rationally and consistently in at least 20 to 80 companies over a long period of time), until 2014 only a limited group of people were allowed access to this asset class. According to regulations of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), in order to protect small investors from unrealistic, high-powered sales pitches, angel investments in the United States were historically available only to those people who qualify under the SEC’s definitions of an Accredited Investor or Qualified Purchaser. Similar rules exist in many other countries that have active financial markets.

In the United States, the definition of both an Accredited Investor and a Qualified Purchaser is specifically set out by the SEC. While there is legalese surrounding both definitions, for all practical purposes you can think of it this way:

– An Accredited Investor is a person who has a steady annual income of at least $200,000 (or $300,000 together with a spouse), or net assets (not including the value of one’s primary residence) of at least $1,000,000.

– A Qualified Purchaser is a person who has at least $5,000,000 in investable assets, or else manages at least $25,000,000 for other people.

Throughout this book I will refer back to this definition of Accredited Investors, the class into which practically all angel investors traditionally fall.

. . . And Who Should Be an Angel?

Because angel investing should be only one part of a well-balanced portfolio, most angels do not (and should not) invest more than 10 percent of their assets into such ventures. In fact, John Huston, the former Chairman of the Angel Capital Association, suggests that angels limit their annual early-stage investments to 10 percent of their free cash flow from other sources. Therefore, in the United States, it is probably fair to say that a typical serious angel investor has invested in between 5 and 10 companies, in amounts ranging from $25,000 to $50,000 each. There are individuals who regularly make much larger investments, and there are many more who invest smaller amounts. There are, however, few angel investors who regard this as a full-time occupation as opposed to venture capitalists, who are, by definition, professionals.

Who are these angels and what drives them?

Angel investors have always been financially motivated (investment by definition implies the expectation of economic returns), although there is often a healthy overlay of social giveback in their calculations. Many active angel investors are, or were, entrepreneurs, which is where they made the money they can now invest. Thus, they are often strong believers in the ethos of entrepreneurship, excited by the prospect of supporting small companies that they believe may one day transform some segment of the business world, spurring economic growth for the benefit of millions. Angels like Reid Hoffman of LinkedIn, Peter Thiel of PayPal, Yossi Vardi of ICQ, or Esther Dyson of EDventure are quite literally changing the world around them. Perhaps the purest case is Tony Hsieh, who has taken the money he made when Amazon acquired Zappos and invested the bulk of it in redeveloping the physical and economic infrastructure of downtown Las Vegas.

However, angel investors by definition are not philanthropists or do-gooders in this area of their lives. Instead, most angels I know are increasingly professional and serious about the economic aspects of the business, driven primarily by the prospect of strong financial returns over the long term.

Angel investing is an area in which the so-called Law of Large Numbers applies. This is a theorem that describes the result of performing the same experiment many times. According to the law, the average of the results obtained from a large number of trials should be close to the expected value, and will tend to become closer as more trials are performed.

The implication of the Law of Large Numbers for angel investing is that any one specific investment is almost by definition going to be unpredictable and, according to statistics, likely to be an economic disappointment . . . but if you invest consistently, intelligently, and over a long period of time, the results are demonstrably repeatable and quite lucrative.

This means that in order to be a successful angel (and, more important, to enjoy being an angel), it is imperative that you have the following personal characteristics:

– Long-term view (measured in years, if not decades)

– Strong economic base and the ability to tolerate losses

– High tolerance for risk

– High tolerance for failure

– Even temperament

– Strong people skills (to deal with Type-A entrepreneurs)

– Self-discipline

– Willingness to learn

– General love and respect for entrepreneurs and startups

There are other characteristics that come into play if you are considering being an active angel, one who spends time working with the company on its operations or strategy, and/or helping the company raise its financing. These include teaching/mentoring ability, domain expertise, business experience, financial savvy, personal networks, and the ability to suffer fools gladly. But the bullet list above generally applies to any prospective angel investor, whether active or passive.

As you may sense, being an angel investor has a lot in common with being an entrepreneur—and entrepreneurship is an inherently crazy business. By making a personal angel investment in one of these by-definition-crazy people, you, as the angel, have voluntarily entered into their Alice-in-Wonderland world of rollercoaster ups and downs, with all of the appurtenant “thrill of victory and agony of defeat.”

From all the angel investments I have made myself, I can just about guarantee that you are going to experience every disaster, disappointment, and insane improbability you can imagine—and more. Because as crazy as each entrepreneur is, you’re simultaneously doing this a dozen or more times! And the nature of the business is that the crazy, disappointing, aggravating, unpleasant, and economically disastrous outcome is likely going to be the default case for 50 to 90 percent of your investments!

So if you are the kind of person who is going to get upset when you lose 100 percent of your $50,000 investment in a promising startup, or can’t deal with the fact that the day after your founder launches a breakthrough product, Google unveils a better, free version that soaks up the entire market, then angel investing is not the business for you to be in . . . just as you clearly should not be an entrepreneur yourself.

Don’t for a moment assume that the warning I’ve just offered is pro forma, or that anything I’m saying does not apply to me. Yes, I have been successful as an angel. And yes, I have experienced my share of failures, mistakes, and heartaches. It comes with the territory. Like every experienced angel, I have many stories to tell about sure-fire winners that went down in flames, as well as my anti-portfolio—opportunities I passed on that turned into major hits.

For example, at an industry conference in 2004 I saw the first demonstration of a device that would take live broadcasts from your home TV and deliver them to you on your smartphone or computer through the Internet, anywhere in the world. I thought it was amazingly cool, and I quickly accosted the startup’s founder, Blake Krikorian, as he walked off the stage. I told him how impressed I was with the product, and asked if he would be willing to come to New York and make a presentation to my fellow investors at New York Angels. He agreed, came to visit us, and demonstrated the system in the Starbucks downstairs from our angel group meeting. We all thought it was amazingly cool, and offered to invest several hundred thousand dollars at a valuation for this pre-shipping, pre-revenue company of something like $5 million.

As I was preparing the term sheet, Blake called us to say that two major Silicon Valley venture capital funds were prepared to invest $10 million at a $20 million valuation for his company—four times the value we’d assigned it! He invited us to participate in that round, and even pleaded with us to invest. But no, we were smart, experienced investors, and we knew full well that a $20 million valuation was simply out of the question for a company whose product hadn’t even shipped, let alone generated any sales. So, despite the fact that we loved the product, that Blake and his cofounder/brother Jason literally begged us to participate, and that some really smart VCs thought it was well worth the high valuation . . . we regretfully passed.

Less than three years later, Sling Media was acquired by EchoStar for $380 million. Ouch!

On the other hand, last year I came across an intriguing startup with an iPad application that was truly state of the art. It brought a novel approach to an existing, large, and lucrative market, and it had a killer founding team. The CEO had been one of the first executives at a major, high-powered public company in the industry, and the CTO had been a mobile engineering leader at Apple, who had brought with him a team of Apple engineers. Both cofounders had personally invested hundreds of thousands of dollars of their own cash already and the prototype they showed us was a combination of sexy and functional. I led the investment round in the company together with a dozen other sophisticated angels, joined the company’s board of directors, and started working to introduce them to potential partners, investors, and customers.

Things seemed to be going well, as the company expanded with our new investment and got ready to launch its initial release. When it did, it was featured in the Apple App Store and got a great many downloads. Unfortunately, very few of them converted into sales that generated revenue. This was disappointing, but not necessarily unexpected. What was unexpected, however, was that less than 90 days after our $350,000 investment went into the company, the CTO/cofounder abruptly gave notice that he was leaving, walking away from $200,000 that he had personally put into the company! Then the whole engineering team quickly followed him out the door. The poor CEO was just as blindsided by his partner’s desertion as we were, and is still struggling valiantly to save some value in the company, but it is now unquestionably an uphill battle. Ouch again!

The funny (or, to be accurate, not so funny) thing is that experiences like this are more the rule than the exception when you enter the wacky and wonderful world of angel investing. Although I didn’t invest when I had the opportunity in companies like Sling Media, Quirky, and Pinterest, I did invest in quite a few companies that went belly-up, taking all my investment with them. In fact, since I’ve made well over 90 personal angel investments, and have been doing this for well over a decade, I’ve had more than 30 companies fail completely. But failure is part of the game, and if you are serious about becoming an angel investor, you need to understand this right up front. The flip side, however, is that I have also had over a dozen exits so far that have returned millions of dollars, and still have many dozens of promising companies remaining in my portfolio. Some of them have recently raised additional capital at valuations well over $100 million, so the overall future value of the portfolio is looking quite good.

If you do have most or all of the angelic characteristics I listed above, and are the kind of person who enjoys uncertainty, competition, mentoring, taking risks, new ideas and technologies, then angel investing can be one of the most enjoyable, fulfilling, and exciting endeavors in which you can engage.

As the statistics suggest, successful angel investing is a numbers game. The odds of any single investment paying off with an enormous return are very small. But if you invest intelligently in enough companies, you have a good chance of having at least a few of those companies become profitable. If they are profitable enough, they will not only pay for the losers, but they will end up giving you a handsome overall rate of return. If done thoughtfully and correctly with a large enough portfolio over a long enough period, the Law of Large Numbers suggests that you will make a much better return than from any mainstream investment class.

Watching the long-term growth of some of my portfolio CEOs has been almost as fulfilling as watching my children grow up . . . and the fact that these heartwarming stories come with a 25 percent-plus portfolio IRR over a decade makes it all the more delicious.

If you are the kind of person who should be an angel investor, you will find it an enormously fulfilling, exciting, mentally stimulating, and economically rewarding activity.

Getting Started in Angel Investing

The SEC regulations governing angel investing have recently begun to shift, opening up new opportunities for startup investing even among Americans who are not at the Accredited level ($1 million in investable assets, or $200,000 annual income). If you fall into this non-Accredited category, then all of your angel investing will be through what the SEC calls online funding portals, as described under Title III of the JOBS Act of 2012. (I will discuss these new platforms and the emerging world of equity crowdfunding at greater length in Chapter 20.) However, as of the date of publication of this book, none of these portals have actually begun operations, because the SEC has not yet finalized the rules that will regulate them. (Of course, you can still buy emerging public companies on the stock market like everyone else.) The general theories about startups and investing presented throughout this book, however, still apply to this new method of investing, although you will find yourself operating in a more constrained (and therefore simpler) environment.

On the other hand, if you already qualify as an Accredited Investor, you can legally invest in startups today, and this book will walk you step by step through the specific steps you can take to make your first investment.

One of the best options for a new angel investor today is to join a local angel investor group, where you work collegially with 25 to 250 other serious investors to hear presentations from companies, do your due-diligence homework, and then—if you are interested—pool your money with the others to make meaningful investments. While most of these groups meet in person and invest primarily in companies based in their region, there are an increasing number of virtual groups, meeting and investing online across geographies. (I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of angel groups—and their investment process—in Chapter 17.)

If you want to strike out on your own, however, this book will walk you through everything you need to know to find opportunities (Chapter 5), do your due-diligence homework on the opportunity (Chapter 8), negotiate the terms of an investment (Chapter 11), and continue to add value during the term of your investment and beyond (Chapter 13).

This a great time to become an angel investor because the past few years have seen the establishment of a number of online platforms that aim to make the process more streamlined. The largest and most comprehensive of these is Gust, which I founded to provide an online infrastructure for the whole angel community. Most angel groups today, in the United States and internationally, use Gust to manage all of their investment operations, and the platform allows group members to easily collaborate both internally and externally on finding and executing investments.

Other websites specialize in specific industries such as real estate (Realty Mogul), films (Slated), consumer products (CircleUp), and the like; specific deal sources such as accelerator programs (Funders Club) or university alumni (Harvard Business School Alumni Angels); specific regions (Seedrs in Europe); or even specific types of investments such as so-called Main Street companies (Bolstr). There are also a host of general platforms that cover range of industries (such as AngelList, EarlyShares and MicroVentures.) As the world of angel investing continues to expand and diversify, more and more online opportunities are sure to arise, either as independent platforms or by functioning as curated groups or collections on top of an existing platform such as Gust.

So getting started as an angel is becoming easier than ever. But what must you do to get started successfully? What kind of strategies do successful angel investors employ to make the numbers work in their favor?

There is no one answer to that question. Trying to generalize about angel investors is like trying to generalize about clouds: they share some fundamental characteristics, but after that, things differ.

One characteristic of most successful angels is a tendency to specialize in industries they know well. While I know some opportunistic angels who will take a flyer on a social networking site one day, a urological catheter the next day, and a sushi/steak restaurant at the end of the week, they are the exception rather than the rule. They tend to be rich people who have lots of money that they play with on a whim, rather than make a considered attempt to generate financial returns.

Most professional angels (that is, people who would self-identify with the term angel investor and are ultimately planning to do ten or more investments) invest in business arenas they already know well. That is why most serious angel groups tend to cluster around particular industries. For example, in New York we have, among others, New York Angels (tech-ish), Tevel Angels (Israeli-related), Golden Seeds (women-led), and New York Life Science Angels (self-explanatory). Other groups specialize in business sectors like space, entertainment, pharmaceuticals, consumer products, big data . . . the list goes on.

Experience, backed up by a number of studies, has shown that if you invest in an area to which you bring background and expertise, you do better over the long run than you would by putting money into a deal which sounds sexy on the surface but would not pass the “sniff test” for someone knowledgeable in the field. Keep in mind, though, that these are not hard-and-fast rules. Businesses in my own portfolio range from animal-lover social networking through zero-gravity space tourism, but they are all areas that I understand. On the other hand, that’s also why I haven’t invested in any drug discovery, restaurant, or film deals.

Another characteristic that virtually all successful angels share is a constant search for the “big vision” investment. Look at the numbers I presented a few pages back. You can see from this breakdown that, to be successful, an angel needs at least one or two really big winners to make up for the many losers a portfolio is almost certain to include. This is why angels aren’t shy about looking for businesses whose equity value they expect to grow at a rate of ten times or twenty times during the next several years.

As a novice investor, you want to avoid the common mistakes made by first-time angels:

– Investing in one of the first deals they see.

– Not doing thorough due diligence.

– Investing outside their domain of experience.

– Investing at too high a valuation.

– Investing on an un-capped convertible note.

– Signing the company’s documents without having a lawyer review them.

– Not reserving additional capital for the inevitable follow-on round.

– Investing in fewer than 20 deals.

– Becoming an angel without a long-term (10 years or more) commitment.

– Dragging out the investment process unnecessarily.

Some of the terms I use in this list (convertible note, follow-on round, and so on) may be unfamiliar. Don’t worry—after you read a bit further you’ll understand what you need to know about them (they’re also listed with explanations in the glossary at the end of the book). Then you’ll be prepared to return to this list, something you may want to do several times before you actually write your first check for an angel investment.

The bottom line is that this is a great time to start thinking about investing in high-growth, startup companies. Whether you’re an Accredited angel investor or a non-Accredited crowdfunder; whether you want to invest with a group or on your own; whether you want to meet founders in person or do everything online; whether you want to invest $1,000 or $1,000,000; whether you want to lead an investment syndicate or participate along with other investors; there are—or shortly will be—groups, platforms, and services that will be delighted to help you get into the game.

Risks in Angel Investing

Because angel investing is still outside the mainstream (as compared with investing in blue-chip stocks or a well-known mutual fund), the idea may make you or your spouse a bit nervous. Frankly, if it doesn’t, you may actually be too much of a risk-seeker to exert the discipline needed to make money in this asset class! The anxiety of unfamiliarity may be compounded by the uncertainty of investing in small companies with modest (or no) track record that you may never have heard of before. So a realistic understanding of the risks in angel investing is critically important before you decide to take the plunge.

One worry you may have is that your money will be stolen by a con artist—that a company founder might simply abscond with your investment funds. In practice, this is exceedingly rare. Although there have been one or two cases where a portfolio CEO turned out to have a problematic past or proceeded to misappropriate funds, this is highly unlikely to happen to you. Keep in mind that angels or VCs fund only a few thousand early-stage companies each year, out of hundreds of thousands that seek such funding (and millions more that start up without seeking funding), which means that such investments are usually exhaustively vetted.

A venture capital firm typically engages in a process that lasts several months, familiarizing themselves with the company, its staff, operations, customers, and financials. (Remember, the funds are going to a company, not someone’s personal checking account.) The venture fund would typically have one or more seats on the company’s board of directors and receive monthly or quarterly financial reports. Trying to abscond with a large amount of cash shortly after a financing event would be a major felony and the investors would, without question, spare no expense to track down the miscreant, who would likely end up in prison for a long time. I’m not aware of this ever having happened.

Angel investments, without a venture fund in the mix to provide a professional level of due diligence and background checks, can be somewhat riskier. But the underlying issues are the same, and after investing in more than 90 startups, and watching hundreds of others, I have never seen this happen. Not once.

Types of Angel Investors

There are almost as many different types of angel investors as there are public market investors. Many people who are angels are also concurrently entrepreneurs in their own right. I’m a serial entrepreneur as well as a serial angel investor, and I’d guess that at least a third to a half (perhaps more) of the members of New York Angels are also currently running their own startups. They range from an air-taxi service to a pubic relations platform, from a medical review website to advertising-technology services.

Many other angels are executives at Fortune 500 companies. Unless there are specific competitive or ethical issues with a particular investment, from their employer’s viewpoint there is no difference between investing in a private company and a public one.

Some angels have retired from the legal or medical professions or from a corporate executive role. Others have inherited the capital they use to invest. They are young and old, male and female, of every race and ethnic background, and located in every state of the union and countless nations around the world. What they all have in common is a readiness to work hard, do their homework, and take calculated risks in pursuit of exciting business opportunities. If you are the right kind of person to take the plunge, I promise you that angel investing will be one of the most stimulating and personally rewarding activities you will ever enjoy.

Get started investing in startups with Gust's Angel Guide. Education, community, and vetted deal flow.

This article is intended for informational purposes only, and doesn't constitute tax, accounting, or legal advice. Everyone's situation is different! For advice in light of your unique circumstances, consult a tax advisor, accountant, or lawyer.