Why Every Angel Needs to Invest in at Least 20 Companies

[The following is an edited excerpt from David S Rose’s book Angel Investing: The Gust Guide to Making Money and Having Fun Investing in Startups.]

When people hear about the 25 percent annualized rate of return that active angel investors obtain, they assume that there must be some secret involved—perhaps an old-boy network of hidden links that connects angels to brilliant entrepreneurs and tech innovators or a mathematical algorithm developed by some genius at MIT that helps angels identify and invest in the businesses that are guaranteed to be the Apples, Googles, and Facebooks of tomorrow.

In reality, there are few secrets about the investment world, including the world of startups. But there are some little-known truths that serious startup investors (both angels and venture capitalists) take for granted, and to which most people—including entrepreneurs themselves—are oblivious. These deal with the fundamental nature of the industry, and one needs to completely internalize them if you are going to be successful at investing in startups.

Get started investing in startups with Gust's Angel Guide. Education, community, and vetted deal flow.

Truth 1: Most Startups Fail

It’s a message that most angels or venture investors could deliver to would-be entrepreneurs dozens of times a month—and that they would deliver were it not for the fact that they don’t want to burn their bridges or ruin their reputations for being nice guys. The message runs something like this:

I’m sorry, but your business idea simply doesn’t make sense. It shows zero understanding of startups in general, your market in particular, and basic economics. Even if your plan made sense, you appear to have no ability at all to execute it. As a matter of fact, the best thing I could do for your own good is to tell you that this is a ridiculous, useless pitch, and you should really forget this whole entrepreneurial thing and go get a job somewhere.

I know, this sounds harsh. That’s why this message is very rarely delivered in precisely this form.

But let’s do the math. Forget the fact that, according to the US Small Business Administration, venture capital (VC) funds invest in fewer than 1 in 400 companies who pitch them. Let’s talk instead about angel investors, who are more prolific, less picky, and individually see fewer opportunities than large venture funds. Tracking data from Gust shows that angels invest in roughly one out of every 40, or about 2.5 percent, of the companies they see. So what about the other startups?

Going down the scale, figure that there is little, if any, difference between the top 2.5 percent and the second 2.5 percent, and that it is almost random as to who gets funded in that top 5 percent. Now, double that number, and figure that the top 10percent would get funded if we could actually match the right investors to the right companies. And because we’re living in a globalized world, with platforms like Gust now connecting many hundreds of thousands of startups and investors, double it again to account for all of the super-specialized tastes, interests, and investing theses that might conceivably get a startup funded. Then, because “all progress depends on the unreasonable man,” to quote George Bernard Shaw, throw in the next 5 percent, because who knows if that wild and crazy idea really is the next big thing?

Add all that up and you’ll see that, being 10 times as generous as the entire angel industry, and100 times as generous as the venture capital industry—we would have funded only the top25percent of hopeful startups. And since the world of business isn’t Garrison Keillor’s Lake Woebegon, “where every startup is above average, ”it means that at least75percentof startups really shouldn’t be funded . . . by anyone, under any circumstances.

And that is the first truth that most angel investors won’t tell you, because to do so would be to spit in the face of the brave, visionary entrepreneurs on whom the angel’s livelihood rests.

Truth 2: No One Knows Which Startups Are Not Going to Fail

The biggest change in my investment approach over years as an angel investor is the one that all serious angels eventually arrive at. I’ve come to accept that, no matter how smart or experienced you are, there are too many exogenous factors affecting business outcomes for you to be able to pick only winners.

Having now invested in over 90startups, my angel investing has been extremely successful. Yet paradoxically, I find that there is little correlation between my home runs and failures—and my personal guesses as to which will be which.

One of my very early angel investments was in a company with the unwieldy name of Design2Launch. The company, founded by CEO Alison Malloy and her brother Ron,developed a digital-workflow solution for the collaboration needs of marketing, creative, and production professionals in the consumer-packaged goods marketplace. Alison was introduced to me in the early days of New York Angels by Stephanie Newby, one of our group’s newer members. Stephanie later went on to found the Golden Seeds angel network, won the Hans Severeins Award from the Angel Capital Association, and is now a rock star of the angel-investing world. Back then, however, she and I were still in the getting-our-feet-wet stage of the business.

Alison’s company at that point had been around for a few years, and was generating revenue from a useful, but rather unsexy product. Shortly before I met her, the company had gone through a rough period of a failed merger with another company, some internal turmoil with a former employee, and a slowdown in sales. Altogether this was not a strong candidate for an angel investment—only four of us out of some 50 members of New York Angels at the time decided to invest. But Alison was smart, passionate, and determined to pull the company back together, she and her brother made a strong team, and Stephanie and I, along with a few other angels, were willing to bet on her.

Because of the rough circumstances, and the likelihood that the company would have no choice but to close its doors if we couldn’t pull an investment round together, we invested a total of a few hundred thousand dollars at a relatively modest company valuation of around a million dollars. For all of us, this was not a bet on the next Facebook or Twitter, but more of a show of faith and support for a deserving entrepreneur in a tough situation. If that year you had asked me to order all of the investments in my portfolio in terms of expected outcomes, Design2Launch would have ranked closer to the bottom of the list than the top.

But quality tells, and often a great entrepreneur can snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. So it was with Alison. Buoyed by our investment and support, she quickly got the company back on its feet, expanded its product line, and forged serious partnerships with some major industry players. Imagine our delight when in the summer of 2008, Kodak, their largest partner, made an all-cash offer to acquire the company for around $15 million!

And here is where things became interesting. For a big-name company that you might read about in the tech blogs, a $15 million acquisition would be tantamount to a disastrous failure. For a company that had made it through one or two rounds of VC financing before failing, an acquisition at that number would be considered a soft landing or an acqui-hire—where the amount received in the sale would reflect primarily the value to the acquiring firm of adding Alison to their leadership team. In any case, the purchase price might be enough to pay back some of the initial investment, but not enough to generate any meaningful return for the company’s founders or investors.

In this case, because of the tight ship that Alison ran, and the modest valuation at which we had invested, the acquisition produced a roughly 10x return for the company’s angels! When I cashed that check for nearly $1 million (the first real payout I had received from one of my angel investments) I realized (a) that it was possible to make money in this asset class, and (b) that it’s possible for a seemingly unimpressive investment to turn into a home run.

A few years later, I invested in a company called CE Interactive, the brainchild of a highly successful serial entrepreneur with extensive experience in the consumer electronics space. He had recently stepped down as CEO of the previous company he had founded, which had become the largest online electronics parts supplier in the world, with customers including virtually every major consumer electronics retailer. His new idea was farsighted and brilliant: to create a database with detailed information about every single piece of consumer electronics equipment, and use it to generate a variety of products, such as instant, illustrated instructions about how to connect all the different electronics in one’s home.

The company had a big vision, a great management team, a solid track record, and widespread support, including from the Consumer Electronics Industry Association itself (the first and only time in its history that the industry had made a commercial investment), and from a top tier, seed-stage VC firm. One of the company’s signed customers was Circuit City, then the largest consumer electronics retailer in the country. It seemed that there was little chance of this being anything but a megahit.

But there is a saying:“Man proposes, but God disposes.” Within a few years of our investment, (1) the company struggled to find an adaptable and scalable business model; (2) maintaining and improving the database platform proved to be more costly than anticipated; (3) Circuit City, the company’s largest customer, went out of business; (4) the economic crisis of 2008 made it virtually impossible for the company to raise additional capital; and (5) the recession put pressure on all of its other retail customers, who cancelled their pilot programs. By the summer of 2011 CE Interactive was out of business, taking with it our entire investment.

Smart investors are aware of their inability to pick only winners, and this distinguishesprofessionals from amateurs. I always smile when I hear tourist angels boast about how they’ve only made two or three investments “and they are all home runs.” Whenever you start thinking that the experts pick all the winners and only winners, stop by the anti-portfolio page on the website of top-tier venture fund Bessemer Venture Partners. Here you will see a list of companies in which the nation’s oldest venture fund declined to make an early investment: Apple, eBay, FedEx (they passed seven times!), Google, Intel, Intuit, Compaq, PayPal, Cisco, and more.

Oh, but you’re more astute than the folks at Bessemer, right? Think again!

Truth 3: Investing in Startups Is a Numbers Game

To recap: most startup businesses aren’t worthy of investment, and no one, regardless of experience or expertise, is capable of routinely identifying which startups areworthy of investment and which are not. Despite these facts, angel investing—when done correctly—really can produce a consistent IRR in the 25 to 30 percent range.The way to achieve this is to invest intelligently in many companies, which has the Law of Large Numbers working on your behalf.

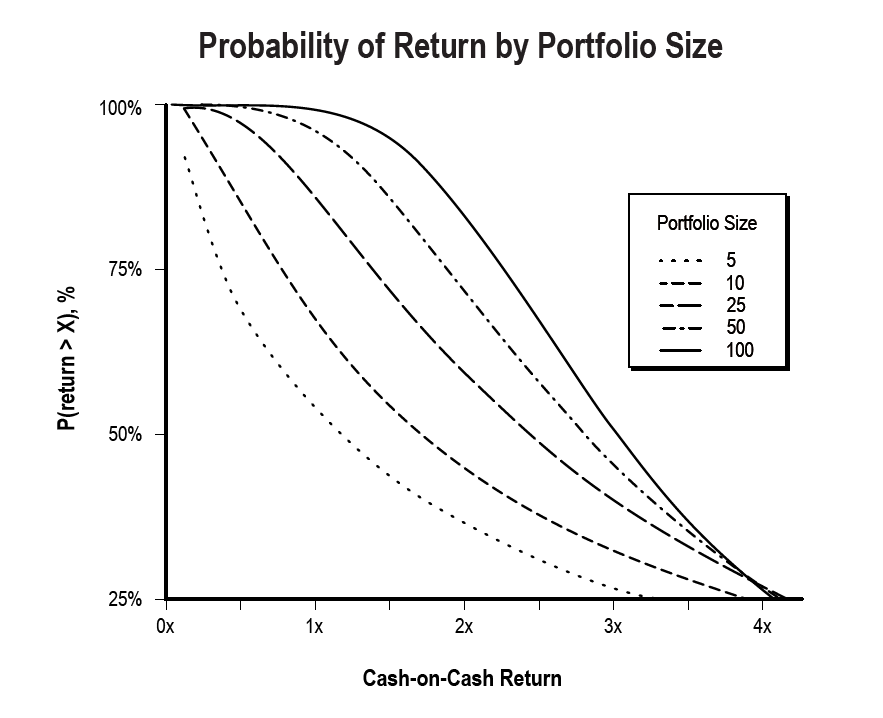

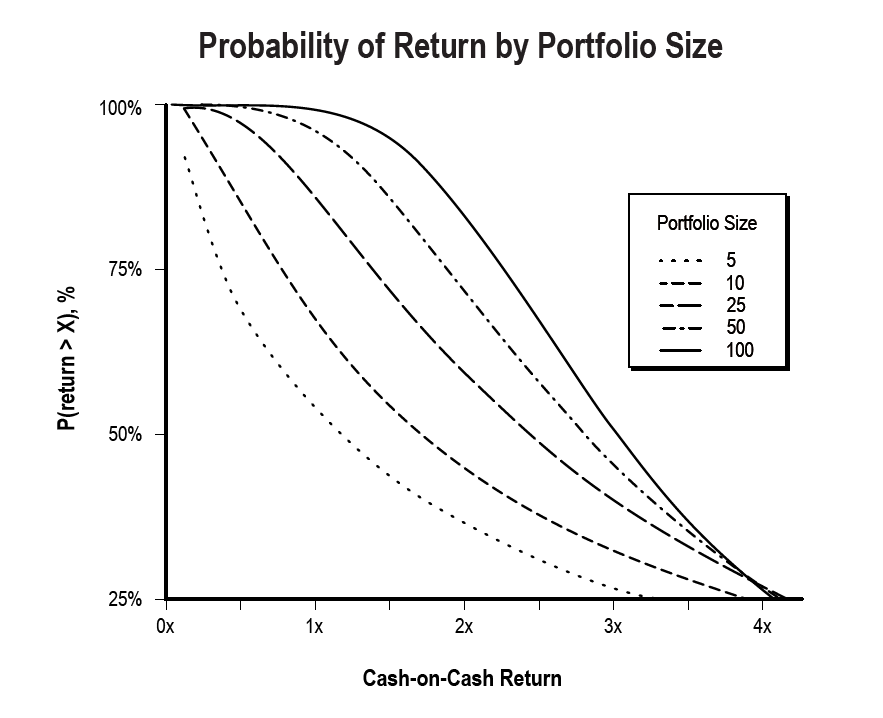

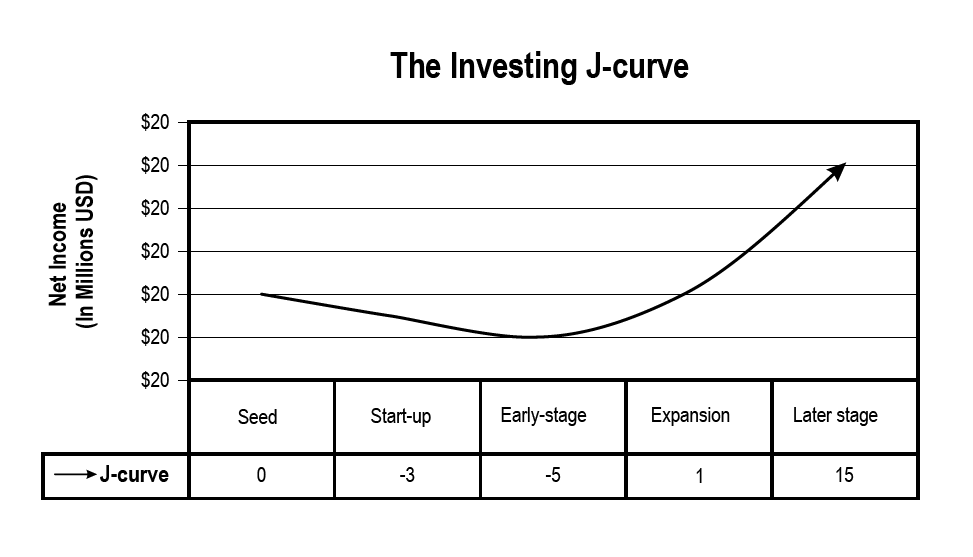

Several studies and mathematical simulations have shown that it takes investing the same amount of money consistently in at least 20 to 25 companies before your returns begin to approach the typical return of over 20 percent for professional, active angel investors. This means the greater the number of companies into which an angel invests, the greater the likelihood of an overall positive return. Sim Simeonov, a veteran software-industry entrepreneur and angel investor, has produced a detailed proof of this thesis, see Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1 Probability of Angel Returns Based on Portfolio Size – Source: Data Driven Patterns for Successful Angel Investing by SimSimeonov,www.slideshare.net/simeons/patterns-of-successful-angel-investing-8306787.

It shows that because of the hits-oriented nature of angel investing, even though any one particular company has roughly similar odds of succeeding or failing, the lopsided nature of the returns means that, on balance, the more companies in which you invest, the more likely your whole portfolio is to generate higher returns.

Truth 4: What Ends Up, Usually Went Down First

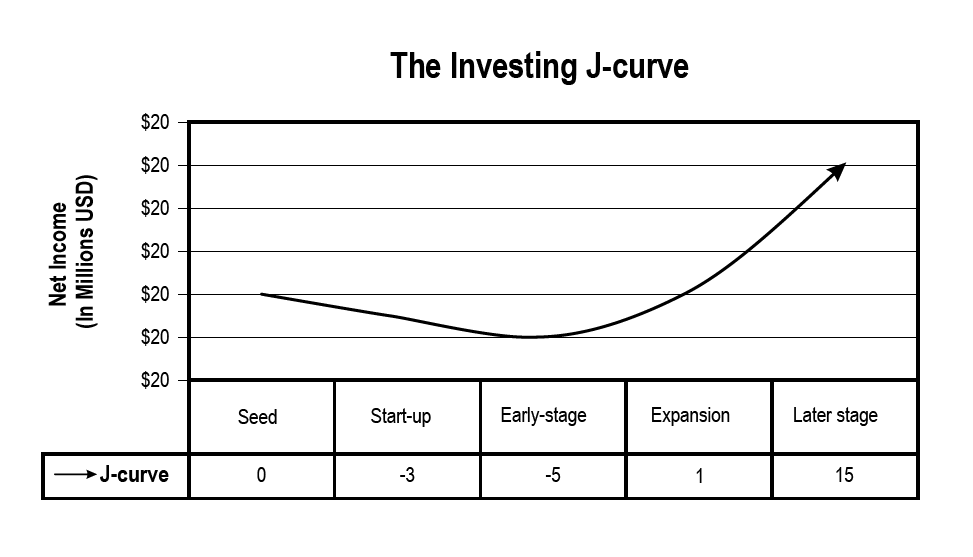

Angel investing (like venture capital) follows the classic J-curve. Because unsuccessful companies tend to fail early, and big exits from the successful ones tend to take a long time to develop, when you graph it on a timeline, the overall value of an angel portfolio makes a shape like the letter “J.” Itbegins dropping for several years as soon as you start investing, and only after a fair amount of time does it change direction and begin to be worth more than the original investment (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 The J-Curve Graph for a Startup Investment Portfolio[Figure3.2] – Source: Townsend, David M. and Busenitz, Lowell W. (2009) “Resource Complementarities, Trade-offs, and Undercapitalization In Technology-Based Ventures: An Empirical Analysis (Summary),” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research: Vol. 29: Iss. 1, Article 5. http://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/fer/vol29/iss1/5

Since the average holding period for an angel investment in the United States is nine years, after only five years it is likely that the value of your angel portfolio will still be underwater, unless it happens to include one unusual, Black Swan, quick, home run. The fact that early profitability is so rare is personally frustrating and likely to cause strain on your marriage. But just as parents survive the terrible twos by remembering that their contrary toddler will eventually morph into an adorable, parent-worshiping three-year-old, you can help yourself through the early dark years by keeping in mind the right-hand side of the chart.

This also means that in addition to investing in a large number of companies, it is a good idea to spread those investments evenly over a long period of time. Venture capital funds typically operate on a five-years-in/five-years-out philosophy. That is, once a VC firm raises a fund, they will spend the first five years putting the money out as investments, and then begin to harvest the returns from those companies that have exits. They will also, around that time, start raising their next fund, so that they always have fresh money to invest.

Similarly, you should decide upfront how much money you are comfortable with investing each year in angel opportunities-such as 10% of your free cash flow-and mentally commit to maintaining that level for 5 to 10 years. That should be long enough to get you through the bottom of the J-Curve and up to the right, where you have a chance of funding future investments from past successes.

Truth 5: All Companies Always Need More Money

Companies always need more money. It doesn’t matter what the founders’ projections are, or how fast they believe they will turn profitable. They will need more money. Although there is the rare case where the company becomes an overnight smash hit and needs more capital than expected to meet overwhelming customer demand, that is true in perhaps 1 out of 10 cases. For the rest, the odds are that the entrepreneur was too optimistic, and/or exogenous factors negatively affected the path to profitability. In either case, however, early investors aren’t usually beating down the doors to throw in more money.

Therefore, the company will typically provide incentives for its investors to participate in these follow-on rounds. These incentives invariably come at the expense of the early investors who choose not to participate . . . which is why venture capitalists always reserve the same amount as their initial investment to put in later into the same company. Unless, as a serious angel, you are planning to reserve a certain amount of your angel-investing capital for follow-ons, your interest in the company is likely to be significantly reduced over time (a phenomenon referred to as equity dilution).

Truth 6: If You Understand and Follow Truths 1 to 5, Angel Investing Can Be Very Lucrative

I realize that much of the foregoing sounds daunting, not to mention taking a lot of time, effort, and commitment to deploy capital over a long period. But there is a light at the end of this particular tunnel:

– If you are an accredited investor, and

– If you are prepared to invest at least $50K to $100K per year, and

– If you make sure to reserve quite a bit for follow-on financings, and

– If you develop a strong deal flow of good companies, and

– If you invest consistently so that you have at least 20 companies (ideally quite a few more) in your portfolio, and

– If you are professional in both your due-diligence investigation and your deal-term negotiation),and

– If you go in with the knowledge that you are going to be in it for at least a decade, holding completely illiquid assets, and

– If you can help add value to your portfolio companies above and beyond simply money, and

– If you follow the advice on all of the above that I’m going give you the following chapters…

then the odds will be in your favor to join the rarified band of successful, professional angel investors who show average IRRs over their investing years of over 25 percent per year.

Get started investing in startups with Gust's Angel Guide. Education, community, and vetted deal flow.

This article is intended for informational purposes only, and doesn't constitute tax, accounting, or legal advice. Everyone's situation is different! For advice in light of your unique circumstances, consult a tax advisor, accountant, or lawyer.