Second-Class Investor Citizens: Facebook’s IPO and Dual-Class Equity Structures

Dual-class voting structures are receiving a lot of attention these days along with intense publicity related to the Facebook IPO, following in the wake of other recent tech IPOs with a similar structure such as Zynga and LinkedIn. This is nothing new; long favored by family-controlled media empires such as Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, among Internet firms alone, Google took a dual-class approach when going public in 2004. Some commentators have suggested this is the wave of the future, signifying a shift in the balance of power from investors to founders of the relatively small, elite group of growth companies that make it to public markets. Yet I’m skeptical that a widespread shift will occur anytime soon, and for reasons discussed below, as much as I admire and advocate for talented entrepreneurs, I believe it would be a losing proposition for nearly all involved.As a quick review, most startups begin life as corporations with a single class of equity securities, referred to as Common Stock, issued to founders, employees, and outside service providers. Options and warrants, when issued, are also typically exercisable for shares of Common Stock. By contrast, venture capital and angel investments normally take the form of Preferred Stock with rights and preferences set forth in the company’s Certificate of Incorporation and other governance documents. A typical series of Preferred Stock in a venture-backed startup carries a liquidation preference, anti-dilution rights, dividend preference, a separate vote to fill its own seat(s) on the Board of Directors, “protective provisions” requiring the company to obtain a separate vote of the Preferred to take certain corporate actions, and more.

If these terms sound onerous and lopsided, it’s because they are. From the point of view of a venture fund that stands to lose some or all of its investment in a portfolio company, putting up $2 million or $10 million of cold hard cash for the entrepreneur to spend building a risky early-stage, pre-revenue venture, justifies significant preferences and protections that Common Stock holders, who invest only “sweat equity” and can theoretically move on to greener pastures at any time, don’t enjoy. Nevertheless, these preferences aren’t intended to last forever. If and when the company goes public or gets acquired in an eligible transaction (as defined in the documents), everything is carefully structured such that virtually all special rights and preferences fall away; the securities convert to a single class of Common Stock, which is listed on an exchange or system such as Nasdaq and traded by the public. (In the case of an acquisition, the shares are tendered for cash and/or stock in the acquiring company.)

Ordinarily, every share of Common Stock in a public company is identical, carrying one vote per share on matters put to any vote of stockholders. To the extent meaningful control survives an IPO, it’s in the form of large blocks of shares held by founders, early investors or others who control enough votes to elect directors at the annual meeting of stockholders. (Although there is no unified SEC definition of “control,” in a public company context, ownership of 10% or more is often considered enough to wield some control.) There are also many anti-takeover devices available to companies when they go public that put the initial Board at great advantage in terms of preserving control going forward.

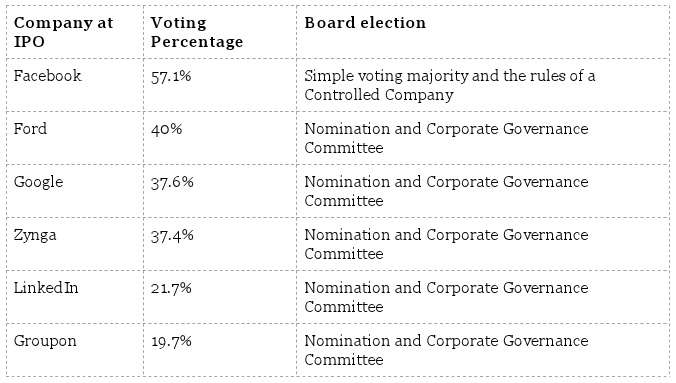

With all that governance out of the way, let’s take a look at Facebook as the most recent, and most extreme, example of the dual-class voting structure. As incumbent CEO owning 28% of the company’s stock — an extraordinarily high percentage for a company valued at $100 billion or more — with his own appointees also dominating the Board, Mark Zuckerberg would already “control” Facebook for most purposes as a public company.  Yet in connection with the IPO, the company has adopted a dual-class structure in which Zuckerberg’s super-voting “Class B” shares will account for 57% of voting power. Management control is further entrenched by other provisions including a “controlled company” designation, exempting the company from the customary stock exchange-imposed corporate governance rules that apply to the vast majority of public companies in the post-Sarbanes-Oxley era. The linked table above from Charley Moore’s opinion piece at TechCrunch illustrates how Facebook compares against several other founder-controlled companies.

Yet in connection with the IPO, the company has adopted a dual-class structure in which Zuckerberg’s super-voting “Class B” shares will account for 57% of voting power. Management control is further entrenched by other provisions including a “controlled company” designation, exempting the company from the customary stock exchange-imposed corporate governance rules that apply to the vast majority of public companies in the post-Sarbanes-Oxley era. The linked table above from Charley Moore’s opinion piece at TechCrunch illustrates how Facebook compares against several other founder-controlled companies.

In addition, the charter documents provide that, if and when the Class B shares ever fall below a majority of voting pose, the board of directors will become “classified” (serving staggered terms), and shareholders will automatically lose the rights to act by written consent, fill vacant seats on the Board, and amend certain provisions of the corporate charter or bylaws.

If all of the above seems too dry and abstract, the Facebook S-1 filing does a good job of explaining in plain English:

Mr. Zuckerberg has the ability to control the outcome of matters submitted to our stockholders for approval, including the election of directors and any merger, consolidation, or sale of all or substantially all of our assets … Additionally, in the event that Mr. Zuckerberg controls our company at the time of his death, control may be transferred to a person or entity that he designates as his successor.

In other words, the practical impact of corporate governance rights, as reflected by shareholder input into any decision made by the company, its Board of Directors or management — already minimal in the case of most public companies, notwithstanding decades of strident protest on the part of investor watchdog groups and sweeping once-in-a-generation reforms instituted by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 — is reduced to literally nothing, not only while Mr. Zuckerberg is at the helm, but even after his death, when the same awesome power, like an hereditary monarchy, is passed to his hand-picked successor.

Expert commentators in law and business schools have debated the pros and cons of dual-class voting structures for decades. The “con” side should be readily apparent: Entrenching management inherently disempowers individual and even large institutional investors, whose capital the company is entrusted with investing to earn a return. Corporate management is a classical “principal-agent” relationship in which management’s objectives can and do diverge from the goals of investors — most strikingly when it comes to managers’ own compensation and job security. The best, if not only, argument in favor of governance arrangements that effectively eradicate investors’ influence on a corporation altogether is that the short-term pressure of Wall Street to meet quarterly and annual earnings and other growth targets can conflict with the long-term best interests of the company and its shareholders.

In practice, shareholder rights get short shrift primarily because the remedy most readily available to aggrieved investors is simply to sell the stock. To take one example, as long-suffering Yahoo! shareholders are keenly aware, effecting change at the Board level can be a long, slow, uncertain process. If successful, a turnaround can take years while investors evaluate progress quarter-by-quarter.

Some companies have succeeded over the long term with a dual-class voting structure that preserves the founder’s (or founding family’s) control at the highest levels. Nevertheless, the sort of iron grip memorialized in Facebook’s governance structure, lasting a lifetime and beyond, seems unprecedented. As a matter of symbolism, it smacks of outright contempt for financial investors. A company that was dragged kicking and screaming into being publicly traded in the first place continues to clutch at every vestige of cloistered, family dynasty status. Although I am an enthusiastic fan of Facebook’s brilliant business and technical execution, sustained over a period of several years’ explosive growth while my own “alma mater” MySpace cratered, I could not in good conscience invest my own funds in a public company that treats even institutional investors’ billions as an afterthought.

This article is for general informational purposes only, not a substitute for professional legal advice. It does not result in the creation of an attorney-client relationship.

Gust Launch can set your startup right so its investment ready.

This article is intended for informational purposes only, and doesn't constitute tax, accounting, or legal advice. Everyone's situation is different! For advice in light of your unique circumstances, consult a tax advisor, accountant, or lawyer.